Intersections of the Heart & Soul; My Return to Dzilth Na O Dith Hle (Part Two)

Written by Stacy Montaigne AuCoin

The school sedan, with Lois at the wheel, delivered us to the Albuquerque airport with plenty of time to spare. Lois and the grade school teacher who traveled with us had errands to do for school, but they accompanied me to my gate, and waited for my flight’s boarding call. I was grateful. They, and others, had become my community and home. Our bonds were braided together from countless shared experiences during my stay at Dzilth Na O Dith Hle school, and by the landscapes that spoke deeply to me within the Diné (Navajo) Nation. Within this community of people and spaces, and the journey of my gradual acceptance, I was changed….

*****

So many memories live within me still, dear reader…. During my first month at Dzilth, I accompanied the third grade class to my first powwow. I was thrilled to go. About 50 dancers and singers filled the spacious gymnasium where it took place. The dancers wore traditional beaded, leathered, ribboned, and feathered finery. The thrumming drum beats, the startling singing, the joining of dance steps that played with the rhythms were powerful and unlike anything I had experienced before.

Our school group rode the old yellow school bus there. Entering the auditorium before the dance started, we passed men, women and children gathered in family and friend groups, talking, and adding the final touches to their costumes. Those coming to watched began to settle into the bleachers. The third grade girls led us; and teacher, bus driver, and I followed them to the very top row of the grandstands. An excellent high perch for watching the drum & singers circle, and the entire dance floor. We were all excited. The girls were beaming and goofing around. Little did I know they were sweetly contriving.

Turns out the girls submitted my name for public recognition at the powwow, as someone who had come from far away. When my name was called over the PA system, it generated impish laughter and delight from a full row of my dear third-graders! “Stacy AuCoin,” the baritone voice boomed over the loud speaker. I froze, preferring the role of anonymous spectator. As the announcer added “her friends from Dzilth Na Oh Dith hle school in Bloomfield say she has come from far away and they’d like her to be recognized.” Playfully narrowing my eyes at the girls, I mouthed the words, “What did you guys do!” They laughed and beamed at me, well pleased with themselves. “Where is Stacy AuCoin?,” asked the announcer. The girls gestured for me to climb down the bleachers and onto the stage below where a man was standing with the microphone. Really? I took a deep breath, raised my hand, and stood up. I’m not entirely sure how I made it down the steep risers to the floor below. Gingerly I made my way down, trying not to step on anyone. Finally, I joined the man with the microphone and he asked me where I was from. Speaking into the microphone, I answered, “Washington, DC.” Loud boos erupted from the crowd! Washington, DC was not a popular place to be from!

I think the man with the microphone made some joke to lighten the mood. I kinda laughed and waved at everyone, and began to work my way back up the steep bleachers. My heart pounded in my ears and my legs felt wobbly. It was tough going, stepping carefully, trying to avoid people and keep my balance. I could feel everyone’s eyes on me. A heaviness lay in the air as if ghosts occupied the narrowing space. The ugliness of our colonial history—the fear, anger, and resentment—pressed in. And then part way up the bleachers, succumbing to the intensity in the room, I fell hard and gashed my shin on the edge of the bleacher seats. I heard someone gasp. My eyes watered, and I stifled a cry. The impact tore through my jeans, gouged my leg and I was bleeding. Thankfully, even at 18, I knew the rooms’ feelings spoke to a dynamic and history so much bigger than my person. They were expressions of deep pain, suffering, and resentment that come from hundreds of years of European colonialism in North America. The violence and greed of Manifest Destiny and the reductionist view of nature as inert resource had devastated a system and way of life for many communities and societies that had lived within the diverse landscapes of North America for thousands of years. I am grateful that in this moment at 18, I had at least some understanding.

Determined not to be undone by the energy in the room or to appear rattled, I put away the pain in my shin and my pride, straightened up, and mustered a dignified climb up the bleachers, back to the top, and back to my third-grader friends. While I climbed, I sensed something happen between me and the rest of the room. A conversation with no words, which I could not have articulated with any cognitive understanding at the time. But I knew something happened. Many years later my friend Ed Duran, a psychologist who works with trauma, an author, and a member of the Apache Nation, suggested I might consider that moment as a “blood offering.” I could see that it was.

I’m not suggesting I needed to diminish myself with guilt about the past. I don’t know of anything good that has ever come from guilt. Guilt only tethers us tighter to a pattern, a narrow repeating eddy, that cuts us off from the main flowing channel of health and vitality. I am suggesting that for me, in this moment in the powwow, I was presented with an opportunity to meet up with the pain of the past. In that moment, in my own small way, I gave drops of my blood as acknowledgment for all the blood spilled in the past. For the pain our humanity suffers.

Humanity’s violence comes from our woundedness. The wound lies within the victim, of course, but there is a tearing of the soul for the aggressor too. When multi-generational trauma isn’t made conscious and healed, the deep wounding perpetuates. Cycles and cycles of trauma repeat. It has to stop. I intuited something of this at 18, and that dawning understanding helped me get through the powwow experience without refueling the cycle of anger, resentment, or fear. In this way the powwow was a catalyst for my own growth…and I am grateful. I’m also grateful for Ed Duran’s suggestion which helps me to make the transformation more conscious.

*****

The Albuquerque Airport was busy with people and PA system announcements. I was grateful Lois accompanied me to my gate at the Albuquerque Airport. In the 1980s airports allowed friends and family to accompany passengers to their gates, before security threats changed all of that. I just couldn’t imagine saying goodbye to Lois yet. We had traveled extensively together throughout the Diné (Navajo) Nation. She took me to Window Rock, the Nation’s headquarters, and we traveled to the Grand Canyon too. She allowed me to drive on our trips, which delighted me then because I seldom drove at home in DC. And now we hung out at the airport gate together, Lois, as lighthearted as always, and the other teacher keeping us in stitches. I was happily lulled into a suspended animation which pushed away the eminent goodbyes.

******

One of the richest experiences for me happened within my last month at Dzilth. I was introduced to a Navajo elder named Mary, who made traditional clay pots. We made a connection of the heart that still lives within me. She called me “granddaughter” after our day together. She claimed me with that name, and a thunderclap echoed inside me, like the thunder that shakes the arid lands of New Mexico and ushers in the spring.

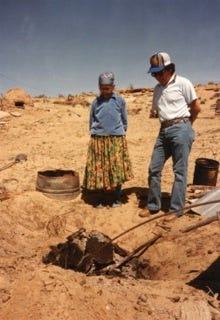

Mary’s son John, a teacher and the head of maintenance at Dzilth, was the one who had introduced us. He had invited me to go with his daughter to his mother’s house for a visit. Mary’s house was a weather worn rectangular structure—simple, neat, utilitarian. The land had arisen and curled around the location of her house. The ancient lava flow long ago had hardened into smooth, rounded mounds that interconnected, spreading out for an acre or more.

Mary’s velvet blue shirt draped heavily over her petite frame, the sleeves rested thickly on her slender wrists. The traditional long skirt rippled when she walked. Her house smelled like the moist earthy pots she made. Kneeling on the particleboard floor before me, her eyes looked into me through thick glasses. I kneeled on the floor opposite her. Behind her, a well-used broom rested against a wall near the oven. A giant earthen pot sat next to her. With its open rim resting on the floor, its rounded bulb sat upright, like the shoulders of an ancestor joining our circle.

Mary made her pottery with local clay that she rolled into coils. Looking to her, I gestured to the pot, and rubbed my hands together as if rolling the clay into long snake-like shapes that I had learned from my high school ceramics class. I lifted my eyebrows to ask if this was her process. Through thick-rimmed glasses that seemed too wide for her slender face, she held my gaze a moment and smiled. She rubbed her hands together like I had and nodded. From then on we were completely absorbed in our non-verbal conversation. John would fill in explanations from time to time. She showed me the deep fire pit, where she covered her pots in semi-dry animal dung. Smoldering hot, it baked her pottery like a kiln. She also used the pitch of pinion pines to glaze and waterproof her pots. I soaked up all that she was sharing. We had tapped into a language that resides behind vocabulary and grammar.

Before we left Mary’s house that day, we helped her get lunch ready. She warmed up homemade stew for us, and a plate of fry bread lay at the center of the table. I remember I was enormously hungry that day; I hadn’t eaten earlier. Mary’s food made my mouth water it was so good, far surpassing the cafeteria food at school. I watched as everyone tore off pieces of the fry bread and replaced the remainder at the center. I remember working hard to temper my raging appetite so that I wouldn’t take more than my share or look rude. With great care Mary asked John to explain to me the practice of only taking what you need and returning the fry bread to the middle for others. What a lovely community conscious way to live one’s life! Through the years I’ve realized just how wise and powerful Mary’s lesson is. The lessons of holding an awareness of the needs of the community in daily practice, and never taking more than you need.

Several days after our return to Dzilth, John came by to give me a coil pot Mary had made for me. Also, he gave me a letter from her that he had translated into English and penned onto special paper. In the letter Mary spoke about the four directions and that I was her granddaughter. She said that each family member had a pot she had made for them, and that this was my pot. Tears still come when I think about being with my Grandmother Mary. It was one special day that I will never forget.

*****

A voice on the PA system announced the boarding of my flight and it pierced through me. The journey was ending and it was time for goodbye. It felt abrupt. Tears arose and I started to cry, hard. We all said our goodbyes and hugged, and I laughed with them through my streaming tears. I really couldn’t stop crying. We waved as I walked to the jet bridge. And in a few seconds I could see them no longer; I could now only hold them in memory. It’s hard to explain why it affected me so. I found my seat on the airplane and quietly sobbed.

My plane whined as it gathered power, and then it thrust down the runway into the skies heading East. Back to a different home. And into my new budding life.

(To be continued)